Is Efficiency a Virtue?

The time God takes . . . and links to some recent work!

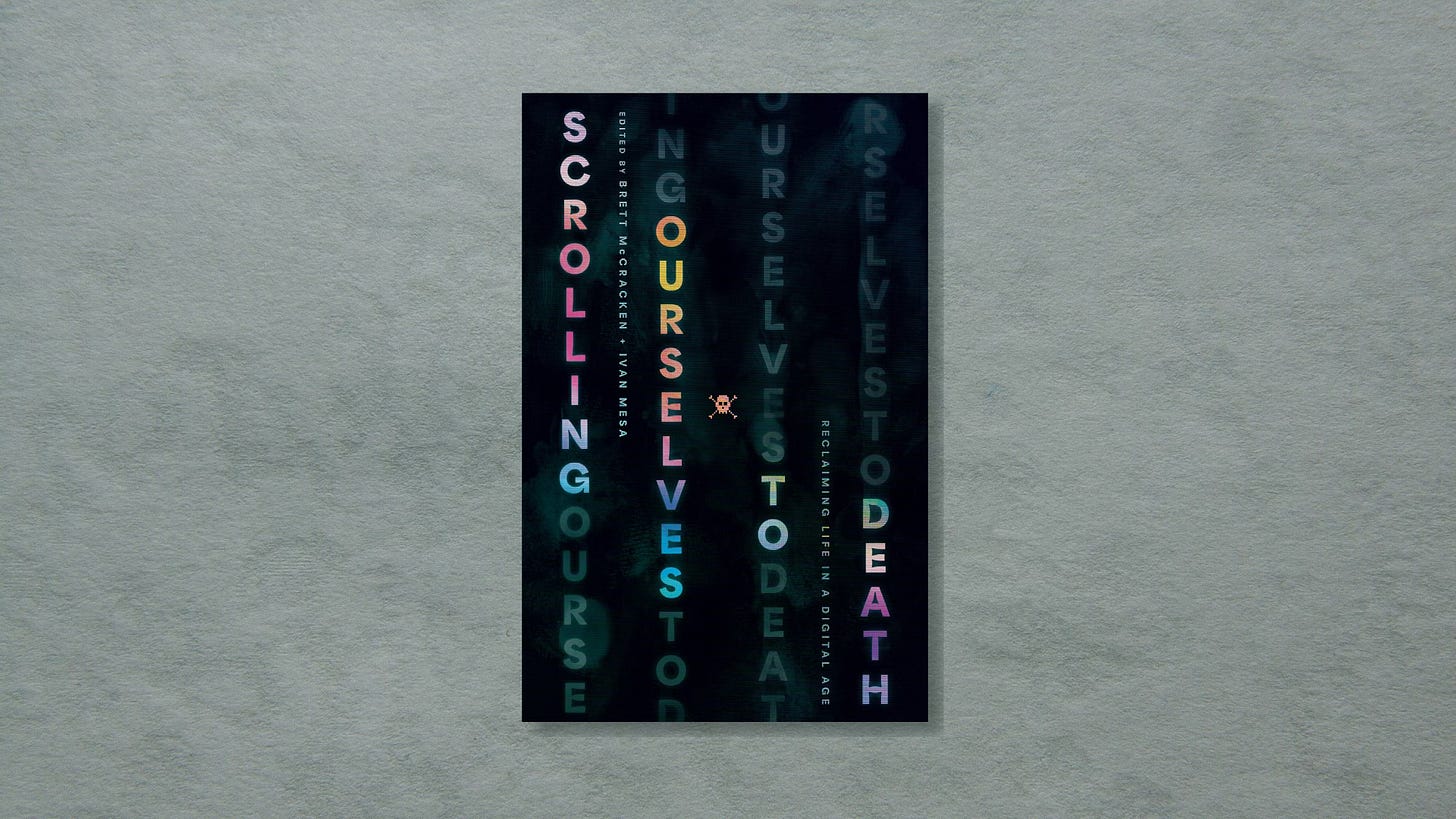

As a quick preview: I hope you’ll get to the end where I share a link ( Passcode: 6yyWK.P.) to an interview with my son, Nathan, whose story I’ve included in a book review, and also tell you more about the collaborative book project to which I contributed: Scrolling Ourselves to Death: Reclaiming Life in a Digital Age.

Last week, I spent so much time “cooking the game” I’ve been catching these couple of years, as I’ve studied Benedict and a rule of life practice. I’ve needed to organize my research, and that’s what I set out to do. I expected the work to be terrible and tedious, and yes, it was tiresome. I wished it had gone faster than it did. But the work, though slow, was mostly generative, as I revisited ideas that had come and gone like migrating birds. There it all was for me, those docile pigeons of insight, in my various notebooks and digital files. I sorted through them slowly and found them each a new home—five Microsoft “braindump” files for each of the five steps I teach in my rule of life workshops.

As I engaged this process of slow and steady work (a direct antidote to more manically driven modes of production), I did some “gentle noticing” of my inward state, as I plodded through days that looked like arriving at the job site and sorting my tools. I was planning to build a house—yet no holes were dug, no foundation was poured, no walls were framed and stood on their end. I knew it was important work, but the material reward was invisible. I confess there was more than occasional panic about the book I have on deadline. It was not going to get written by organizing alone.

Stepping back from this particular project—and talking to my good Father about the iron fist at the center of my chest—I wondered, in company with God, why I felt so hurried. There was nothing to indicate that I’d be delinquent in turning this book on time. For instance, it’s not like I’m writing this book as a side hustle, like many other writers do. This is my full-time work (or full-ish time work). I have the privilege, especially now that the kids are older, of long, uninterrupted stretches of daylight in which to get words on paper. So why the rush, the hurry, the low-grade panic that I’m already failing the thing when no one is expecting to see my work for another six months?

I can only say that it’s hard to live a more trusting story of time. It’s hard because we live in a technological world driven by one goal and one goal alone: efficiency. People tell us we should be doing more, that we should be doing it in less time, that we should be doing it more and more effortlessly especially now that our AI companions are at our side, finishing our sentences for us. (As an aside, this letter is not being written with the help of AI, and this Substack never will be less than human.) When efficiency is your goal, everything can be improved at the factory, never mind that you are not a machine.

I’ve come to think of efficiency as the unqualified good of our time. It’s a virtue whose logic is self-reinforcing. Save time to save time! If you can be more efficient, why wouldn’t you want to be? (Listen to every argument for the good of AI, and it distills down to this.) One problem is this: if efficiency is an unqualified good, we imagine God prizes it as we do. We imagine God’s goals are saving time and avoiding waste. Perhaps we also imagine we hear the drumming of the divine fingers, the audible divine sigh when we must be reminded—yet again—of the lesson we were supposed to have learned last year. Efficiency—as noble ideal—makes God an impatient and irritable being, frustrated that we can’t move faster and master our transformation and his mission more quickly.

But this is not the God revealed in the Scriptures. Our God is patient, gentle, uniquely acquainted with the time it takes to live a human life in a world that suffers contingency. This God lingers over the work of creation, taking light then sea then land then vegetation as numbered, daily tasks. There was evening, and there was morning, the first and second and third day. The formerly formless void might have blazed up in a sudden, efficient instant, innumerable galaxies and universes, hewn and gleaming. But God works at the world like a master builder, never fretting that the work isn’t already completed. He’s not threatened by an empty job site. In fact, he’s so committed to this long project that he hands it off to us. Go, make more of this place!

Time is the essential ingredient in the story authored by this God. Do not miss this. In fact, begin reading Scripture as if days and years and generations are a kind of character, moving the plot forward. In the Old Testament, as Marilynne Robinson points out, God’s purpose does not “reveal its whole meaning in the course of any life or generation or era,” (138). Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Joseph: each sees only a glimpse of the unfolding story, and when it’s handed off to Moses, he, too, stands at the edge of the Promised Land at the end of his life to glimpse, not grasp, the promises of God. Faith means unavoidable waiting.

Then, in the New Testament, we have pearls, mustard seeds, yeast. As metaphors of the kingdom, they symbolize the sometimes excruciatingly slow work that God engages in his creative work of repair. The work is sure, but it is so often hidden from our sight. Faith means unavoidable waiting. And maybe that is just to say that God isn’t efficiently moving us toward some material end but to patient trust. We have a good, good Father—and we could not know the steadfastness of his love if every wish and whim of ours were instantaneously gratified. We could not know that he intends a greater beauty in us than a spit polish and shine, a beauty forged in the furnace of time.

I wish, for example, that I’d been able to hurry my own transformation before becoming a mother. Why did my children (especially the firstborn) have to suffer the angrier, more selfish and more demanding version of myself? Well, the years were the occasion for the gentling that has happened in me, as I’ve broken and been broken by the patterns of my sin. I could not have grieved that sin as I do now, and grief is important in change. I could not have been the mother to my firstborn baby that I am now, to my adulting and soon-to-launch children. I’ve learned a few things—and none of them efficiently.

I heard someone say to me recently that they want to get the problems in their marriage straightened out before having kids. The impulse is for sure good. Yes, if you can name and change some of the unhealthy patterns of living together, do that sooner rather than later. But I want to gently suggest a reconsideration, of the good of time. Don’t imagine, I might say, that you’re going to “solve” the thing before little Joey is born. Nope, that baby is birthed into your mess, as much as you wish it weren’t so. But you’ll soon discover how years are an occasion for grace. Had you had it all figured out beforehand, you wouldn’t have needed the love of your good, good Father to cover over the multitude of your sins. You wouldn’t have known just how great that grace is, for sinners like you and also your children.

Squarely in midlife, I know more about the good of time. In fact, this Lent, I’m thinking of just how much time stands between Good Friday and Easter Sunday. Few of us think about Holy Saturday, but it really is wonderful, that day squished between death and resurrection, despair and hope. We’re reminded of the time God takes and the inefficiencies he’s more than happy to engage. Goodness, why not the cross—and straight to Jesus visibly enthroned, ruling and reigning over the world? Get behind me, Satan! You are a hindrance to me. For you are not setting your mind on the things of God, but on the things of man.

Turning a bit now, I wanted to share some recent work that resonates with these themes of God’s slow time.

First, I’ve written a book review of Ian Harber’s Walking Through Deconstruction. It’s scaffolded by a very personal story of my older son, Nathan, who experienced a four-year faith wandering. His wasn’t a typical story of deconstruction; in that he wasn’t disaffected with Christians for their hypocrisy or the church for its political idolatry. He also wasn’t simply dismantling faith to make some life choice that wouldn’t have honored Christian moral commitments. Rather, he was intellectually struggling with important, big questions. I tell some of that story in the review—and also tell some of how God brought Nathan back to faith. It’s such a grace, but it’s a story of time. Time to ask questions. Time to seek truth. Time to wander and find the way home. Nathan and I recorded a Zoom conversation about his story, and maybe it would encourage you to watch it! Please feel free to share, too!

Passcode: 6yyWK.P.

Second, I had the privilege of contributing to a new collaborative project published by Crossway. Scrolling Ourselves to Death: Reclaiming Life in a Digital Age is a work of many hands, including editors Brett McCracken and Ivan Mesa. Conceived as a retrospective on Neil Postman’s 1985 book, Amusing Ourselves to Death, it looks at the prescience of Postman’s work and how we might reclaim a better relationship to technology. My own chapter, “From the Age of Exposition to the Age of Expression,” travels the arc from a print culture to—well, this space here. I think this book is going to be really helpful to anyone looking to think deeply about the ways our devices shape us. “Ask not, in other words, what your tool does for you; ask what your tool makes of you.”

Thanks as always for taking time to read here, at A Habit Called Faith!

So much packed into this piece. Your words are a gift to me in this season of motherhood with 3 littles. So much slow work, but reminded of our God who works masterfully in the middle of it. 🤍

“Years are an occasion for grace.” How beautiful and true!!! In this season of Lent I’m trying to pay attention to my wandering…. The ways I quickly move away from the time the Lord may want me to sit, be present and wait in.. to reflect back on the years that have been filled with bitter and sweet and see them full of His patience and grace for me. Sharing too with a friend whose son is wrestling with His faith. Thank you again Jen for sharing honestly and beautifully.