Reading Genesis with Marilynne Robinson

Here's your January nudge to read the Bible this year.

It is January, which means you will find me reading my favorite book of the Bible: Genesis. In 2025, I’m not attempting to read the Bible in a year, which has generally been a staple spiritual practice for me since college. (I like recommending the One Year Bible in the New Living Translation, if case you’re interested in starting.)

Instead, I’m spending my mornings reading a poem and a psalm, then lingering more carefully and closely over one of the books of the Bible I’m studying: Acts with my church, 1 Samuel with a friend, and now also Genesis with Ryan and a couple from Toronto, whom we miss. (I never read all of these at the same time, by the way!)

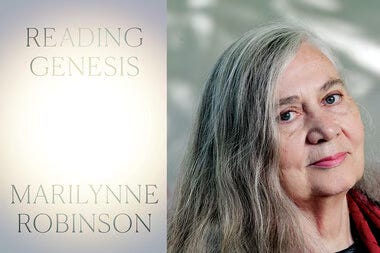

With our Toronto friends, we’ve decided to pair our reading of Genesis with Marilynne Robinson’s Reading Genesis, which I wouldn’t exactly call a commentary on the text but a meditation or extended reflection on this first book of the Bible.

I’m keenly interested in Robinson’s work and will generally read or listen to any interview with her. Last year, she appeared on The Ezra Klein Show as well as The Russell Moore Show to talk about Reading Genesis. By her own account, Robinson has been deeply influenced by the 16th-century reformer John Calvin, and it was the Institutes she spent reading between her first highly acclaimed novel, Housekeeping, and the novels that followed twenty years later (Gilead, Home, Lila, Jack). Robinson is a deeply committed Christian, though not one conformed to the social and political conservatism of much of American evangelicalism.

It’s taken me this long to finally begin Robinson’s book on Genesis, which begins like this: “The Bible is a theodicy, a meditation on the problem of evil.” I had never thought to characterize the Bible in this way, but to stand back, it makes a lot of sense. The first two chapters of the Bible read like an idyll, and everything that follows describes how far the good world has fallen from what it once was.

What Robinson finds so curious, in the early chapters of Genesis, is why humankind continues to be so central to the divine project, even after the tragedy of their betraying his command. “God’s perfect Creation passes through a series of changes,” Robinson writes, “declensions that permit the anomaly of a flawed and alienated creature at the center of it all, ourselves, still sacred, still beloved of God” (3). In essence, Robinson draws attention to this exceptionality of the text, that God continues to pursue covenant love with Adam, with Noah, with Abraham, Issac, and Jacob. Isn’t there enough evidence to say they’ll fail any mission with which they’re entrusted? That God (and we as readers) can count on their dignity and freedom being horribly abused?

I think there are two particularly wrong-headed ways of reading the Bible: one secular, the other “Christian.” Robinson is good at addressing the first of these misguided readings, the secularist who assumes that the text represents an ancient and therefore primitive viewpoint. The secularist assumes that the Hebrew Bible is derivative, borrowing its stories from the ancient Babylonians who told their (earlier) stories of creation and flood in similar terms. Genesis is entirely uninventive, the secularist often says, a text crudely composed by cut and paste.

But Robinson knows enough—about the Bible and ancient Babylonian literature—to say that these are lazy assumptions. It’s the Bible’s “departures” from the ancient myths, it’s the differences at their points of most common resonance that prove most telling. In the Babylonian stories, the humans are not inherently good or made in the image of the gods. They are good insofar as they are of divine “use.” And the gods themselves are not good like the God who speaks in Genesis; except for their power (exercised capriciously), they are are too coarsely human. What characterizes the ancient Babylonian myths are their obvious “fabulousness,” their un-realism. But by contrast, the world of Genesis unfolds in the most banal of ways: fathers and mothers begetting sons and daughters and God loving these flawed human families.

Maybe this is one reason I love Genesis, because the drama of the narrative, especially as it introduces the story of Abraham, feels so entirely human. There are the predictable plot twists at moments of jealousy and wrath, fear and carnal pleasure. This story is moving forward exactly as it should, on the one hand, when fallen human beings are so central to the action. I love Genesis for how recognizable and real it all seems.

But this isn’t merely a human story. No, in the beginning, God. Hovering over all the events, there is a Creator, a Sustainer, a Keeper, a Redeemer, and when the story seems doomed by human sin, he’s rescuing the action, somehow allowing for a human freedom that yet does not thwart his purposes. It’s to say that this book reads nothing like the ancient Babylonian myths, where the world is on the gods’ tight leash, which they will painfully yank at will.

The paradox is that God is the author of this story, though humans seem also to be acting with real moral responsibility (and really making a mess of things). Robinson describes it this way: “Adam and Eve disobeyed, doubted, tried to deceive. These are all complex acts of will. The old Christian theologies spoke of felix culpa, the fortunate fall. This is in effect another name for human agency, responsibility, even freedom. If we could do only those things God wills, we would not be truly free, though to discern the will of God and act on it is freedom” (19). If you’re struggling to understand how to reconcile God’s providence and human freedom, welcome to the narrative landscape of the Bible, which invites us to believe that the decisions of our lives matter even if God’s purposes will not be deterred.

It brings me, briefly, to one wrong-headed “Christian” reading of the Bible. In an attempt at reverence, even worship (and perhaps to try resolving the tension of the aforementioned paradox), some say that God and God alone is at the center of the Bible. They diminish human beings, reminding us that we are nothing, mere worms in the grandeur of it all. God doesn’t need us! They don’t want us getting too big for our britches, too self-aggrandizing, too self-preoccupied. But let’s be honest: how do you not read Genesis and avoid the temptation to think more highly of yourself? What is this story where God comes to a man named Abram and determines to bless him and make his family great?

To be sure, the kind of high anthropology that the Bible is illustrating is not part and parcel of the self-esteem movement. No, there’s nothing in the text to suggest that we aren’t deeply flawed, deeply corrupt, obstinately turned away from the goodness of God and his intentions for us and the world. You’re not reading the story right if you don’t absorb what happened in Genesis 3 when we were exiled from the Garden on account of our rebellion against God. But neither are you reading the story right if you don’t marvel like the Psalmist, “What is man that you are mindful of him, the son of man that you care for him?” Too high an anthropology is a misreading of the story, but too low an anthropology is its own distortion. Humankind is made in the image of God, and when that image is marred, God goes on a rescue mission of the highest stakes. I like how Chesterton puts it in Orthodoxy: human beings are “chief of creatures, chief of sinners.”

To read Genesis is to begin to absorb the fantastic improbability that you have garnered the attention of the God who spun the world into being. Not because you are good: because you are not. Not because you do good: because you do not. You are loved and noticed and cared for by God because this is simply the way in which God has ordered this world. He has made human beings, endowed them with his image, and covenanted to love them despite the risk involved. We know that the story of Genesis points forward to how the biblical story will eventually finally climax, that Jesus Christ will give his life to put this unfathomable love on offer to all who would receive it (John 1:12).

Yes, you can and should read the Bible to know you are horrible and wicked. (You living your self-intuited truth might just be the worst idea of 2025.) But please, also read the Bible to know that God loves because he loves, that despite your unworthiness, God loves you. I think this is the truth that might matter most in your Christian life. Because if you cannot believe God loves you, you cannot trust the good he has for you. You will not pray, you will not obey his commands, and you will not lose your life in order to save it. Robinson summarizes this truth in this way: “[The disobedience of Adam and Eve] is a failure of trust in His benevolence toward them,” (28). She might well have been thinking of Calvin, who opens his Institutes with a meditation on God’s goodness toward humanity and how this compels us in the life of Christian faith:

“For until men recognize that they owe everything to God, that they are nourished by his fatherly care, that he is the Author of their every good, that they should seek nothing beyond him—they will never yield him willing service. Nay, unless they establish their complete happiness in him, they will never give themselves truly and sincerely to him” (41).

There are thousands of reasons to read the Bible, and myriad of ways to engage in the task. I hope I’ve given you one reason here, to discover that the God of Creation has set his love on this world. Only the self-giving love of God has the power to transform you, sustain you, comfort you, give you the sense of wholeness for which you are searching. Read the Bible this year: maybe beginning in Genesis and continuing in John.

It would be a fruitful way to begin another year.

Some of you might not know, but I have written a book, A Habit Called Faith, that tells the Biblical story through a close reading of the books of Deuteronomy and John. This might also be a helpful resource to you, and it may be a book you put on your list for Lent this year!

There are still a few spots remaining in this week’s upcoming Rule of Life workshops: Friday, 11 am EST – 3 pm EST, and Saturday, 9 am EST – 1 pm EST. Find out more here.

I thought Reading Genesis could equally well have been titled Enjoying Genesis, for Robinson’s intent is clearly not to quibble about textual details or rehash the same old arguments. And I enjoyed the reminder that God loves people much more than we give him credit for as evidenced by his great constancy in honoring his word and acting in alignment with his revealed character and attributes.

We are reading through the Bible chronologically with a FB group. Second time for me. NLT. Are you going to post your thought as you read through?