Last night, our church gathered for Scripture readings and hymns, marking that first-century Good Friday when, in a remote corner of the Roman empire, Jesus of Nazareth—Son of Man, Son of God, Suffering Servant—was crucified for the sins of the world. Our service ended as the last candle—the Christ candle—was extinguished and paraded down the center aisle and out of the sanctuary. I could feel the darkness descend at the moment: the darkness of Holy Saturday, when hope was, if only momentarily, stilled.

In recent years, I’ve thought that more should be said about Holy Saturday, this liminal day between death and resurrection. Holy Saturday seems to suggest the quality of ordinary time: when we wait for God to act (or perhaps don’t even yet know to wait). I wrote about this in In Good Time, and when I woke up this morning, I thought to share an excerpt here. (This will substitute for Monday’s letter.)

In this final chapter of the book, I am reflecting on a recent cancer scare, when I had to return for a repeat mammogram and breast ultrasound:

“But I’m not dying, I learn after that appointment. At least not from breast cancer and not right now. I have been catastrophizing again . . . I know how easily you can accommodate yourself to the fright that the universe is just this threadbare, that you and those you love might fall through any minute. But I also know the paradox that it is not a fright at all. You gain sanity for not hoping in permanence. You grow wise for remembering you will die.

Hope is possible, even here at the bottom—because as a Christian, you understand death is not the end.

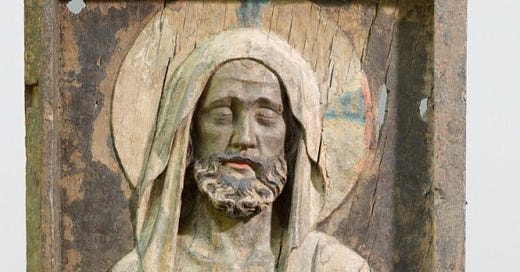

I think of the medieval statue of Jesus awaiting the resurrection that is housed in the Princely Collections at the Liechtenstein Garden Palace in Vienna. The helpful museum staff tells me this statue is called “Christ of the Holy Sepulchre.” . . .1

The statue’s wood is weathered, the paint faded except for the faint red of Jesus’s lips and wounds. He looks as if he is dreaming sweetly behind his closed eyes. What I found so striking about the statue—and why I pestered the curator for more information about it after we’d returned home—was that it was not the sagging figure of Good Friday Jesus, hanging from the cross, nor was it the triumphal figure of Easter morning Jesus, raised from the dead. It was the Christ of Holy Saturday, the Christ of the time being.

The dead body of Christ is laid out as though he was sleeping. His nimbus disc also serves as a pillow, and the corpse is wrapped in a delicate cloth which—except for the chest area with the side wound, the forearms and the bearded face—covers the figure with delicate flowing folds. This hands pierced by the nails of the cross are laid on his thighs with convulsively spread fingers, but the gentle swaying of the body as a whole reduces the impression of rigor mortis.2

Unlike the other Christs of medieval devotional art, this Christ is a waiting Christ.

Reading later about other similar works of the fourteenth century, I learn this life-size statue likely played a role in Paschal celebrations. The priest would have placed a small piece of the host in the open wound of Jesus’s side on Maundy Thursday. Then this small crust of bread would have been retrieved on Easter morning before the church, at the very moment the angelic announcement at the empty tomb was dramatized before the congregants: ‘He is not here. He is risen today!”

Last night, reading the foreword to a book of prayers on death, grief, and hope given to me by a friend who recently lost her mother, I remember the [hope of the resurrection.] “In the face of our own deaths, or the deaths of those we are privileged to know most in this pilgrimage, we all need to be reminded again and again of this great story and its storied end.”3

Christ’s body was broken, was buried—and then was resurrected and retrieved. And the good news, the gospel, of this story is that death is no longer a terror or mortal dread. No, we don’t hope to get cancer or COVID—but we don’t cower in their shadow. If we have believing trust in the resurrected, retrieved, and returning Christ, we are saved not just from death but from our fear of death. Christ has harrowed the gates of hell itself, as the Apostles’ Creed reminds us, and whatever that exactly means (because I’m not at all sure), I think it means we fear not.

Fear not.

According to information provided to me by the museum’s curators, this statue, called “Christ of the Holy Sepulchre,” was sculpted by an unnamed Upper-Rhenish or Western Swiss artist and acquired by Prince Johann II von Liechtenstein in 1909.

Alexandra Hanzl, email to the author, June 28, 2021. Used by permission.

Douglas Kaien McKelvey, Every Moment Holy, vol. 2 (Nashville: Rabbit Room Press, 2021), xiv.

"the Christ of the time being." I love that, and I'll quote you on it. Thanks for this, Jen. Happy Easter!

Thank you…Such helpful and thought provoking words for the place we find ourselves in, the liminal space of the already not yet… “the waiting Christ”… we wait, we long for your return O Christ our resurrected King